Ian Collins | December 2025

Diabetes: The big picture

Diabetes mellitus is a major contributor to illness and death and is responsible for over 10% of U.S. deaths1. The name means “honey-sweet,” referring to sugar in urine, one of the most recognisable symptoms. Risk factors include obesity, high cholesterol, and high blood pressure, and complications range from heart attacks and strokes to kidney disease and disability.

Global cases have exploded from 100 million in 1980 to nearly 600 million today, projected to hit 850 million by 20502. About half of this rise is simply due to population growth and aging. Lifestyle played a role late last century, but in many high-income countries incidence has since stabilised or declined.

The bigger driver of increasing prevalence now is that people with diabetes live longer thanks to better care. Advances in insulin, oral drugs, statins, and glucose monitoring since the late 20th century have dramatically improved outcomes.

Looking ahead, the treatment pipeline is strong: smarter drugs, better monitoring, and even potential curative approaches. In this article, we explore what these developments mean - not just for patients, but for their insurability in the years to come.

Two types, one disease

Diabetes mellitus has two main forms: Type 1 and Type 2. Both cause high blood glucose due to ineffective insulin use, but they differ fundamentally.

- Type 1 is an autoimmune condition where the immune system destroys insulin-producing cells in the pancreas. It usually appears in childhood or early adulthood and requires lifelong insulin therapy.

- Type 2 is a metabolic disorder linked to lifestyle factors such as poor diet and inactivity. The body still produces insulin but becomes resistant to it. It typically develops in middle age and is managed through medication (e.g. metformin, GLP-1 agonists) and lifestyle changes.

Type 2 accounts for about 90% of cases in the UK and US. In both types, excess glucose damages blood vessels and nerves, raising risks of heart disease, stroke, and other complications. 3

In the following sections we look at three different families of emerging technologies, all of which are helping to improve outcomes for diabetic patients. Not all apply to both type 1 and type 2 diabetes. We indicate which developments apply to which type where relevant.

Improved glucose monitoring

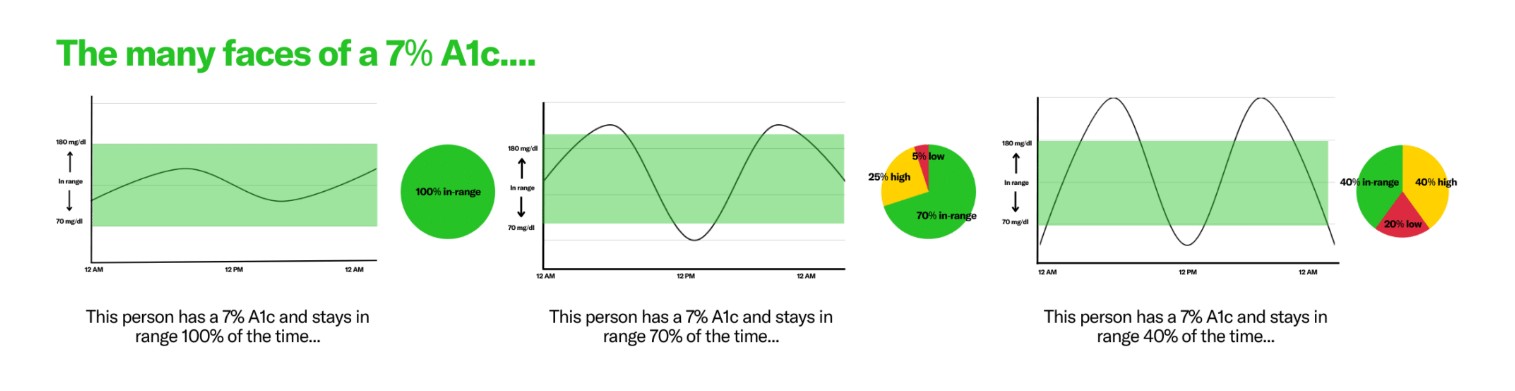

Patients aim to keep glucose within target range. More time outside the range means higher complication risk. HbA1c is the most common measure, but it only reflects average control and can mask dangerous fluctuations (see graphic).4

If keeping glucose in range is critical, then knowing your levels is just as important. The challenge is that glucose fluctuates throughout the day, affected by food, exercise, stress, sleep, and medication.

From the 1980s to early 2000s, most diabetics relied on finger-prick tests at home. Many still do, but the last two decades have brought big improvements. Continuous glucose monitors (CGMs), first introduced about 20 years ago, now provide real-time readings via a tiny sensor under the skin. Modern CGMs alert users when levels drift out of range and help fine-tune insulin doses. Next-gen sensors may use nanotech and AI to predict trends even more accurately.

For the one-third of diabetics using insulin (including nearly all with Type 1), smart insulin pens simplify dosing and track injections, often syncing with apps. These started appearing in the mid-2010s and keep getting smarter.

Then there’s the artificial pancreas: a wearable device that monitors glucose and automatically delivers insulin5. It’s not perfect, but trials show better glucose control, improved sleep, and higher patient satisfaction.

The most futuristic idea is the bioartificial pancreas. Instead of just injecting insulin, this implant would contain living islet cells that produce insulin naturally. It’s still experimental and faces hurdles like surgical complexity and immune rejection, but if successful, it could eliminate daily management altogether6.

New medications

Recent drugs have transformed diabetes care - especially for Type 2 patients - with more on the way. These treatments lower blood sugar, aid weight loss, and even help the body excrete glucose.

One big breakthrough, receiving much recent attention, is incretin-mimetics, which mimic hormones like GLP-1 that regulate blood sugar after meals. Originally developed for diabetes, they’ve become famous as obesity drugs. GLP-1 drugs like semaglutide can dramatically improve control. STEP 2 showed HbA1c dropping from 8.1% to 6.5% in just 12 weeks7. While long-term impacts on mortality and heart health are still being studied, better glucose control should mean better outcomes.

Next up are even stronger options like retatrutide, expected within two years8, plus versions with fewer side effects and oral dosing for easier compliance. Wider access is also likely as supply grows.

Another important class is SGLT-2 inhibitors, which prevent glucose reabsorption in the kidneys. Drugs like empagliflozin show promising reductions in heart failure hospitalizations and overall mortality9.

Another relatively new family of drugs is JAK-inhibitors which may help people with type 1 diabetes. Type 1 disease relates to an overactive immune system. During the early phase of a person’s life their own body destroys cells in their pancreas. When this has happened it is irreversible, but the damage takes many years to occur. New drugs like baricitinib could help preserve some pancreatic function, preventing some of the worst outcomes of type 1 diabetes10.

Remission strategies

Most advances help diabetics manage their condition, not cure it. But some approaches aim for remission, and in rare cases, even a “functional cure”.

The most promising work focuses on repairing or replacing beta cells in the pancreas - the root cause of both Type 1 and Type 2 diabetes. Cell transplants from donors already exist but require lifelong immune suppression and are limited by donor availability. New trials are testing modified cells that avoid triggering the immune system11.

Stem cell therapies are another frontier. In one trial, 10 of 12 patients stopped insulin within a year, though they still needed immunosuppressants. Using a patient’s own stem cells could bypass rejection risk, and early successes hint at real potential. Over 100 trials are underway, mostly for Type 1 diabetes12.

Remission can also come from intensive weight loss. In one study, patients on an 800-calorie diet for 3–5 months saw remission if they lost 15kg but most relapsed within five years13.

The most reliable option today is bariatric surgery, which induces remission in most Type 2 patients, sometimes even before weight loss suggesting gut hormones and the microbiome play a role14. Future drugs may mimic these effects without surgery. GLP-1 agonists already point in that direction.

Insurance considerations and conclusion

We’ve covered a wave of innovations improving life for diabetics, some already in use, others still in development. So, what does it all mean? Here are our three big takeaways:

1. The pipeline of treatment options is strong. From better monitoring and drugs to potential curative approaches, progress is steady. A full cure is distant, but diabetics are living longer, healthier lives, and that trend should continue.

2. Population impact matters. Diabetes drives heart disease, strokes, and other serious conditions. Better management could help reverse the slowdown in mortality improvements seen over the past 15 years. That said, high prevalence of diabetes remains a challenge and these high-risk individuals will still be in the population in the longer term.

3. Changes in how insurers view diabetes. Diabetes was once uninsurable; now most can get life cover with modest ratings. But current pricing relies on old data based on people diagnosed decades ago, before modern treatments. Today’s applicants often fare far better, thanks to tech like CGMs, smart pens, and GLP-1 drugs. Insurers who adapt could offer more competitive products and expand access, even into morbidity cover.

Diabetes is common, slow-moving, and improving fast. Whether future gains come from smarter tech or true cures, the scale of this condition means its impact on health and insurance will be felt for years to come.

References

[1] Number of Diabetes-Attributable Deaths - Burden Toolkit

[2] Diabetes Facts and Figures | International Diabetes Federation

[3] https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/diabetes-mellitus-type-2-complications

[4] Decreasing diabetes-related complications with time in range - Time in Range Coalition

[6] https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa2415948

[9] SGLT2 Inhibitors and Heart Failure Outcomes

[10] https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa2306691

Ian Collins

VP | Medical Analytics

.png)

.png)

.png)