Ian Collins | February 2026

A ‘slowdown’ in mortality improvements is a demographic phenomenon observed in populations of many higher-income countries since around 2010. Cardiovascular diseases contribute significantly to this feature of trend.

A common factor across these markets was a prior sustained period of generally adverse dietary and exercise behaviours leading to measurable increases in both obesity and the prevalence of diagnosed diabetes - sometimes referred to as a ‘diabesity epidemic’. Many commentators believe this helps explain a material proportion of the slowdown.

Trend assumptions in these markets tend to incorporate overlay adjustments, specifically designed to reflect predictions of how this phenomenon may grade off into the future. These adjustments would be informed, to varying degrees, by the many complex factors driving circulatory trend. This includes, for example, the future influence of new weight loss drugs. However, a key contributor would be the lagged impact of known contributors to circulatory deaths, including diabetes.

In this case study we consider whether such an approach be suitable for India, given that market’s unique diabetes risk profile. In principle we argue it would, but there are some market-specific factors to consider.

Diabetes is becoming more common in India

The reliability of population trend data can be questionable, but these strongly indicate sustained rises in both incidence and prevalence of (diagnosed) diabetes over 30+ years. Male age standardised incidence rates for diabetes have increased from ~2.1 per mille in 1990 to nearer 3.5 in 2019 according to data from the IHME.1 A similar pattern is seen for women but with lower rates.

Although the presence of a recent strong upward trend is a familiar one in many parts of the world, some features differ from typical high-income countries. For example, Indian cases rose from a lower base, and increasing trends for prediabetic conditions2 3 suggest a continuing rise in future diabetics is more likely than the plateaued high prevalence rates typically observed more recently in western nations.

There are also markedly different rates within Indian populations. One key differential is the rural/urban divide. Urban diabetes prevalence is approximately twice as high. Not unrelated to this, states with higher levels of economic development tended to have greater age-standardised prevalence.4 Odds ratios for diabetes onset are over twice as high for the richest household wealth quintile compared with the poorest and obesity onset is even more skewed.5

Rural to urban migration over recent decades has been substantial. Indian populations exhibit exposures to health consequences of both low and high weights, but the effect of urbanisation has been to shift this burden towards the obesity end of the spectrum. The picture gets even more complex with relatively strong regional variations reflecting large cultural differences and socio-economic skews.6

South Asian populations are more susceptible to diabetes

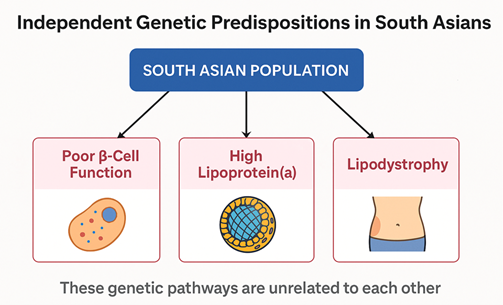

There is strong evidence of a high genetic predisposition to diabetes and other cardiovascular risks in Indian and other South Asian communities. Many genetic variants increase susceptibility to diabetes, some of which are more common among people with South Asian ancestry, including those associated with lower insulin production and less healthy fat distribution.7

Compared with European populations, South Asians tend to be more insulin resistant, meaning their tissues are less responsive to insulin and require higher insulin levels to maintain normal blood glucose. This is accompanied by relatively poor beta-cell function. Genetic variants affecting beta-cell development and insulin secretion are enriched in South Asian populations.

Another driver is lipodystrophy, a propensity to have lower peripheral subcutaneous fat storage and greater ectopic fat deposition (i.e. in the liver or muscle) leading to higher metabolic risk at lower BMI.8

The combined impacts contribute to impaired fasting glucose levels in India approximately double those in most of Europe,9 with some studies suggesting substantially larger differences.10 Studies consistently show that South Asians have a two to four times higher overall risk of developing type two diabetes compared with people of White European descent.11 The wide range in part reflects that the condition can remain undiagnosed for long periods, adding to uncertainty.

Evidence from national studies, comparisons of racial groups, and migration studies (sometimes using sibling pairs to control partially for genetics) support the view that South Asians are particularly sensitive to diabetes onset in response to changes in dietary and environmental exposures.12

Additionally, there is a genetic tendency towards higher levels of lipoprotein(a)13 - an LDL cholesterol variant strongly associated with cardiovascular risk, via atherosclerosis increasing clotting risk and causing inflammation. Lipoprotein(a) levels are mostly genetically determined, stable throughout life, resistant to drugs like statins and are not amenable to behavioural change. This does not increase the risk of developing diabetes but is associated with worse cardiovascular outcomes among people with diabetes.

India is subject to its own trends in adverse population behaviours, including consumption of calorie-dense processed foods, declining physical activity, and rising obesity, all of which accelerate progression from impaired fasting glucose to diabetes. The genetic factors we discuss here make India overall more sensitive than typical western markets.

Looking to the future

Looking further ahead diabetes is becoming much more manageable (see main article). The Indian diabetic population will benefit from these emerging technologies, though access will likely have a strong socio-economic skew. For example, it is likely that India will be a major manufacturer of generic versions of GLP-1 agonist medicines once they come off-patent. New technologies mitigate, but do not remove, risks associated with trends in underlying behaviours which contribute to increasing diabetes incidence.

The trajectory of diabetes in India will therefore reflect the impact of complex interrelated factors, including genetic susceptibility, cultural and lifestyle trends, and access to treatment. These will lead to different patterns in the timing and shape of diabetes trends compared with Western countries. Understanding the relative importance of each factor is key to anticipating Indian trends.

.png)

.png)

.png)